1. Slieve Mish

I spent part of my childhood living in Lisburn, a small city just outside of Belfast (the capital of Northern Ireland). While I was too young to remember any of my first stint there, the latter took place when I was between the ages of 11 and 13. I remember those years fondly: we had a large but cold house, and I spent my school holidays hiking in the Mourne mountains, attending Ice Hockey games—Belfast (still!) have the best team in the UK—and shopping at Hollister. But if I came to understand anything from my time in the North, it was precisely how little I, or British people in general, truly understand about our little, yet historically and politically tumultuous, territory across the Irish Sea.

Even some fifteen years after the Good Friday Agreement officially ended the Troubles—Northern Ireland’s thirty-year civil war—its ominous memory continued to hang over my experience. I lived in a military encampment, and it just so happened that my house was next to the perimeter of the base; from my bedroom window, I could just about peer over the towering walls of concrete, corrugated metal, and razor wire, bristling with CCTV cameras, into the civilian neighbourhood beyond. These glimpses were most of what I saw of the place: I was required to flash my ID at guards equipped with full body armour, submachine guns, and attack dogs to even leave my neighbourhood. Once out in public, I was placed under strict orders of clandestineness: speak in a low voice, wear no clothing with the words “England” clearly on it—even my football socks from the 2012 Euros campaign were expressly banned—and do not, under any circumstances, tell anyone what your dad does for work.

Outside of the personal level, too, I encountered the realities of a country still wholly run by deeply-rooted sectarianism. Friend groups, schools, and entire neighbourhoods were wholly split on Protestant and Catholic lines; unsurprisingly, being an Army kid, the youth camps I went to during the summers were entirely attended by the former group. So divided were the cultures that you could generally tell someone’s background from their name alone, or even from looking at their houses: the stereotype suggests that Protestants almost always have blinds in their windows, while Catholics have lace curtains. Speaking to people from the North more recently, I learned an even more ridiculous dividing line: while Catholics tend to keep their toasters on the counter in their kitchens, Protestants would store them in the cupboard (admittedly, I am still unaware of the reasoning behind this particular quirk). A brilliant scene from Derry Girls highlights just how strongly these divides still express themselves in Northern Irish culture—and, indeed, just about how out-of-place I felt as an English boy deposited in this environment.

As a tween, I didn’t really question such peculiarities, many of which now seem absurd when I recount them to Brits my age—as a military brat, you grow used to obediently adapting to new environments. But while I didn’t properly comprehend the full historical context that led to my circumstances, I think what stuck with me was the collective sense of trauma and suppressed violent tendencies that still pervaded Belfast: the uneasy calm of a former warzone at peace for now, but which could rapidly spark again given the right circumstances. That’s the Northern Ireland I knew. It felt like standing atop a dormant volcano.

My father, my brother and I in the Mourne Mountains. 2014.

2. Tales of the Troubles

Now, I hardly blame anyone my age from Britain (note: as opposed to the UK) for not knowing much about the Troubles, or, indeed, about Ireland itself. The national History curriculum, or at least what I was taught, relatively conveniently circumvents any and all mention of the UK’s violent, crime-ridden colonial past. Even dealing with colonies such as India and Africa seemed to be relatively taboo, never mind approaching something as recent, as painful, and as outright criminal as many of the UK government’s actions in Ireland from the 1970s to the 1990s; going further back, events such as the Potato Famine or the War of Independence were almost wholly ignored, the latter even when I studied World War I and the interwar period in the UK and Europe. The most mention Belfast ever got was for its role in building the Titanic a century ago. On a broader level, such deliberate educational oversight provides a decent explanation, and a worrying precedent, for Westminster politicians’ pervasive lack of knowledge of and attention paid to Northern Ireland (see Brexit, for an emphatic example). It is a history both incredibly relevant to our own country, and which has the capacity to teach us valuable lessons about similar struggles in the world today. Equally, though, I used to think that one could read all the history books on the North and still not quite resonate with it on a personal level; at least, not in the way that I feel I somewhat can after having lived there.

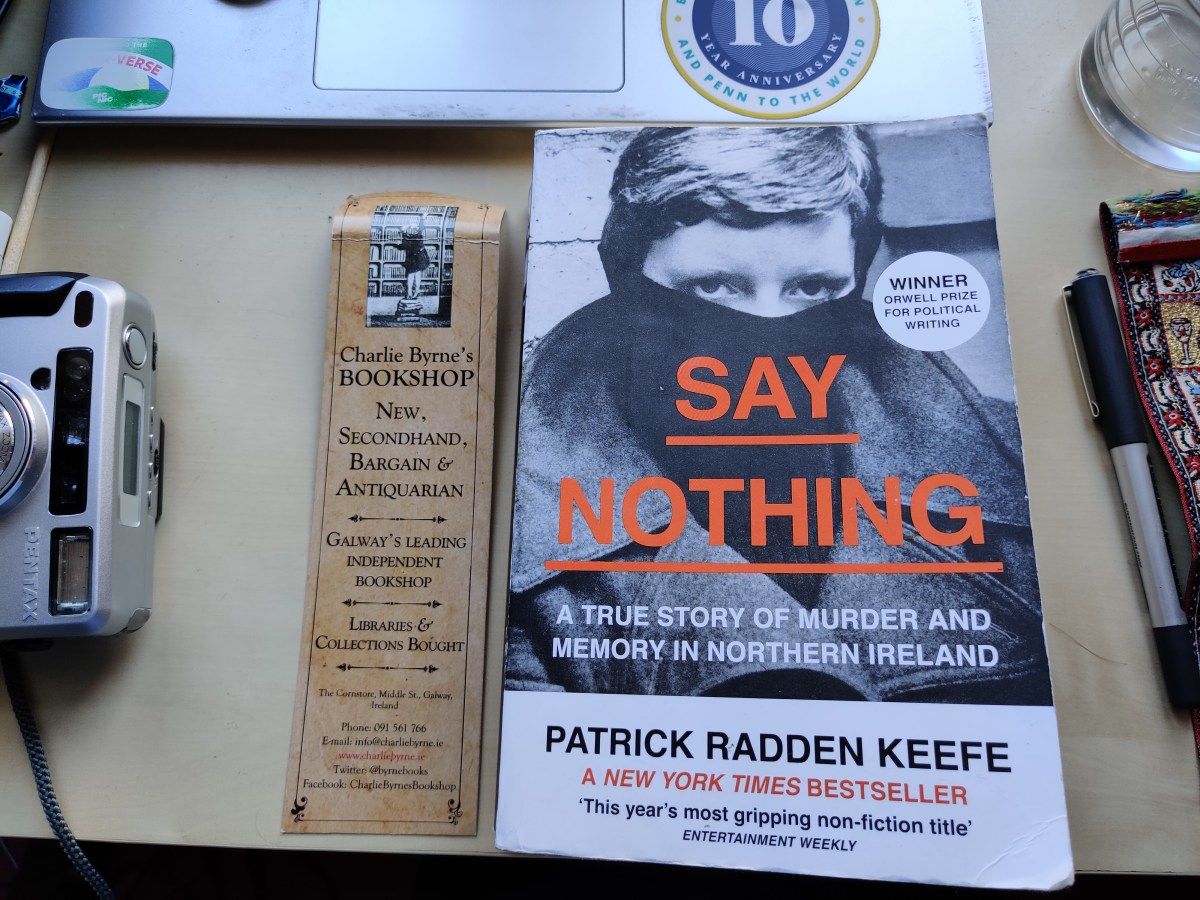

Recent events have changed this view somewhat. In February, my friend Mira came across from the US to stay with me in Edinburgh; having just been in Ireland, she’d picked up an interesting-looking book to give me as a thanks. The book in question was Patrick Radden Keefe’s Say Nothing, an account of the Troubles and the so-called Provisional IRA’s role in them. In short, I was blown away. The thing I think this book executes so masterfully is its choice of tone and structure: rather than merely being a factual history book, Radden Keefe chooses to write in narrative non-fiction. The result is an account of the conflict from the point of view of the complex, nuanced, and fundamentally human people who lived through it. There’s Dolours Price, the daughter of an IRA veteran who moves from peaceful protesting to more radical means. Or Brendan Hughes, the gritty ground commander who sacrifices his marriage and, at times, his morals, for a cause he believes to be unstoppable and fundamentally just. Or Gerry Adams, the later-famous Sinn Fein President who had a murky and contested career in the field. Many more such characters come into the fray (you’ll have to read it yourself to learn about them), but the real narrative hook of the story focuses on the family of Jean McConville, the widowed mother of ten in a mixed Protestant-Catholic family who, one evening in 1972, was suddenly kidnapped by her neighbours and never seen again. Radden Keefe focuses on recounting McConville’s broken family’s story over the following decades, and perhaps unturning some further stones in the mystery of her fate. Using this to provide a centrepoint for the book is an excellent tool for exploring the Troubles’ impact, as well as their memory and how it’s presented, on Belfast’s unwitting and innocent inhabitants.

Now, there is only so much which can be covered without turning into a history textbook: Say Nothing pays little attention to the conflict outside of Belfast and the crimes of loyalist insurgents such as the Ulster Defence Force, while a broader account of how the peace process came to light was also slightly lacking. But the point of this isn’t an accurate historical overview of the conflict: for that, you can go to a textbook or Wikipedia. The book’s aim, instead, is to transport the reader into Troubles-era Belfast by placing them into the stories of the people who lived through it. Aside from this direction allowing the book to provide an account which is riveting and undeniably human—so much so that I tore through the book in two days—it also helps to encapsulate and communicate to the reader that same feeling of division and unease that I often felt when I lived in Belfast (which, incidentally, is the same time that the book was written). That, in itself, makes Say Nothing an absolute landmark. Indeed, I reckon that UK politics would be in a much better position were all politicians—or even everyone—mandatorily forced to read it.

If that doesn’t come as enough of a recommendation, I don’t know what would.

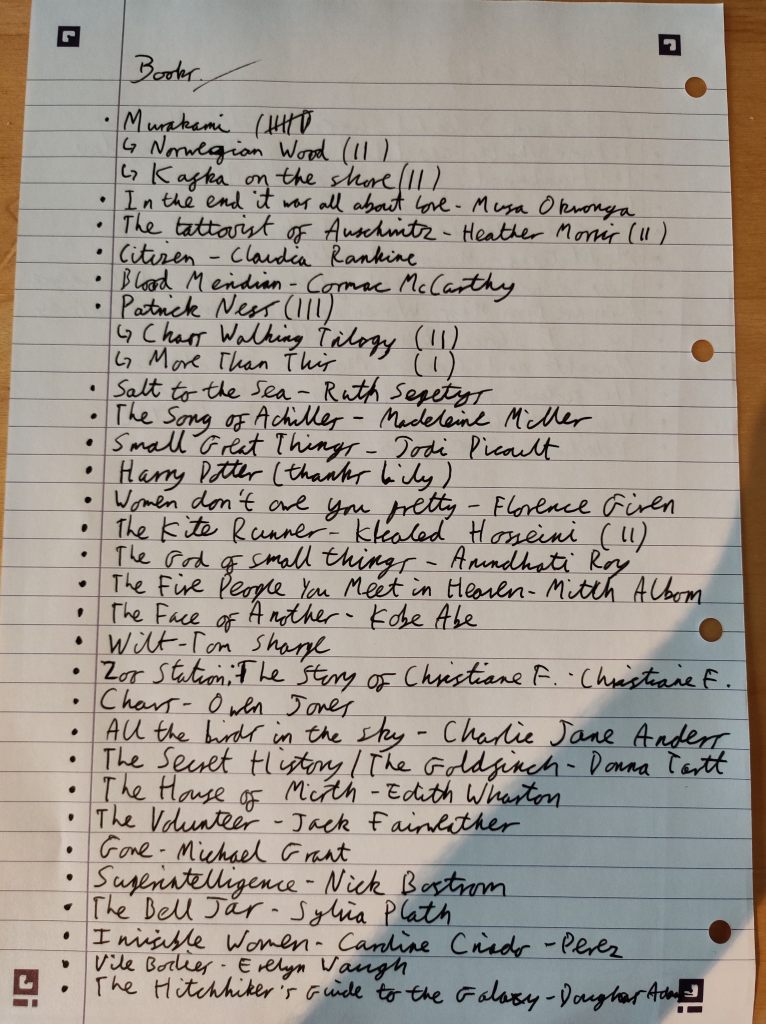

My copy of Say Nothing. 2024.

3. An addendum on Ireland and Palestine

In terms of the lessons we might apply from the Troubles to the modern day, a particular line from Say Nothing really stuck with me. The following is written on p. 259 (in my version):

“Part of the reason that such a process [as truth and reconciliation] was feasible in South Africa was that in the aftermath of apartheid, there was an obvious winner. The Troubles, by contrast, concluded in stalemate”.

Now, I’ve stated several times in the past year that I’m not in the business of presenting concrete solutions to the conflict and occupation in Israel and Palestine: many more qualified and informed people than me have attempted it, and all have failed. But having previously put a lot of weight on South Africa as the best template we’ve got in terms of where on earth to start with a peace process, reading this book gave me a lot of cause for reconsideration. The Troubles, after all, have a lot in common with what we see in Gaza today: an embittered battle between a modernised, Western state army and a generational, rag-tag paramilitary organisation, ostensibly in the name of an oppressed group’s liberation from a foreign force on one hand, and the violent cessation of the rebels’ existence on the other. Neither goal is easily achieved even if it is realistic; war crimes abound on both sides. Crucially, though, outside of the total annexation of Palestine by Israel—an outcome that worryingly seems more and more possible by the day—I don’t see this conflict ending in anything other than a ceasefire and a stalemate. As the Provos knew then and Hamas knows now, overcoming the occupier is impossible; meanwhile, as the UK knew and Israel knows, crushing a rebel movement by force is impossible (though I can say for a fact that this is not the true aim of at least some members of Netanyahu’s cabinet). The issue is, of course, far more complex than this vague outline suggests. But the similarities may render the Troubles one of the best templates we’ve got for working out some sort of just resolution.

As the book details, the Good Friday Agreement was far from perfect. Many victims of the Troubles felt betrayed by its existence, and its terms and spirit have been largely defiled in the subsequent years (cough cough Brexit cough cough). But in providing an adequate political solution focused on amnesty and peacebuilding from both sides, it achieved far more than 30 further years of violence ever could have. Now, I’m not informed enough to offer more of a deep dive into the intricacies of each peace agreement; there are far better resources on that out there. But what I do know is that while the Belfast I knew was divided, tense, and fundamentally haunted by the spectre of its past, at least it wasn’t a bloody warzone. That is the least that kids in Gaza, Kibbutz Be’eri, and beyond deserve right now. Someday, I hope that their stories are told with the same care, and their humanity is as well conveyed, as Radden Keefe has done here.

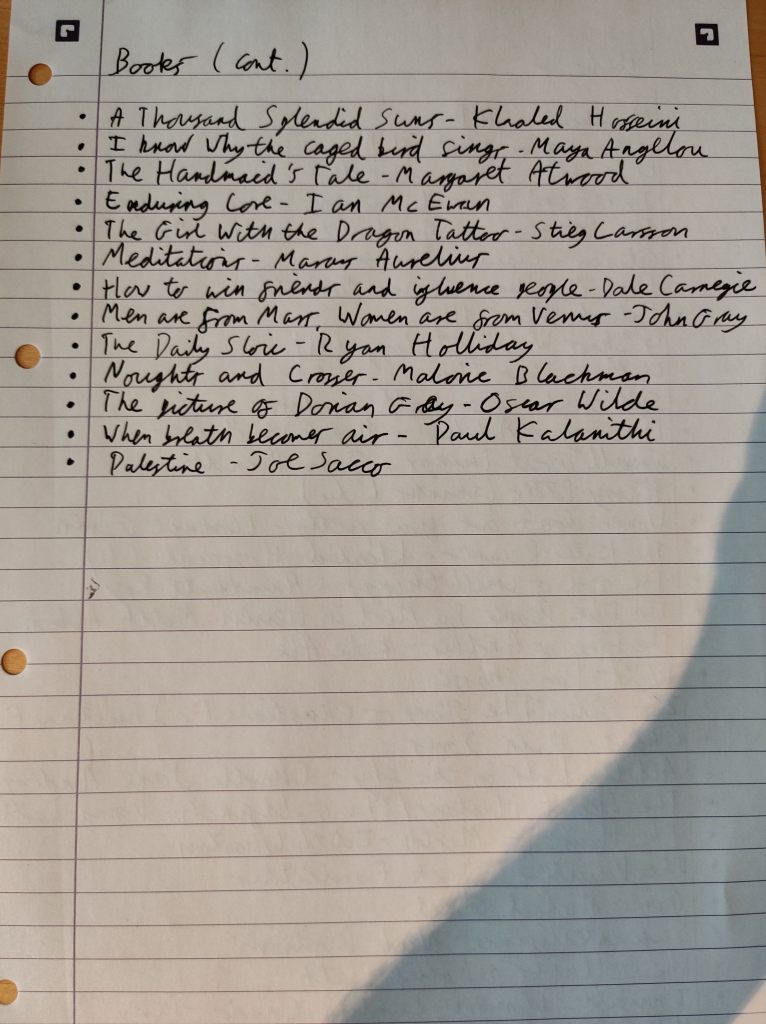

Now, if anyone has any good book recommendations about potatoes, I’d best get reading…

Buy Say Nothing at the Lighthouse here, or through your local independent bookshop.